Nuria García

The safety and quality of dairy products depends not only on the quality of raw milk, but also on adequate handling, distribution, and storage practices. As a result, dairy farms should avoid any type of milk contamination, such as that produced by species of Paenibacillus and Clostridium, two microorganisms.

To establish an adequate strategy to control spores’ contamination of the milk in the bulk tank it is necessary to know where the harmful microorganisms are located, and which are their contamination channels.

Cattle feed is the first source where possible contamination can come from. Plant material that will be fed to cows may be affected by microorganisms during its growth and/or harvest. When these plants are preserved as silage, the increase in the spore population depends on the properties of the individual microorganism, and the conditions under which the silage was put up.

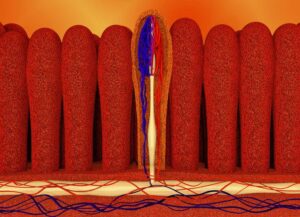

When contaminated silage is included in a total mixed ration (TMR) spores pass through the digestive tract of the cow unmodified and are finally excreted with the manure. Bedding materials used in the barns are often contaminated with cow feces, and when a cow is lying down it is virtually inevitable that bedding and feces will come in contact with the udder, the last step of the contamination before reaching the bulk tank.

A more detailed understanding of contamination pathways, and how microorganisms behave, would identify the most efficient means to improve the control of spores’ contamination in the farm. A study carried out at the University of Turin (Italy; Borreani et al., 2019), addressed precisely this issue.

The study was conducted on 49 dairy farms in the river Po Valley (Italy), whose milk production was used for cheese making. The experiment was designed to detect the presence of anaerobic spore-forming microorganisms (they do not need oxygen to survive) and facultative anaerobes (they use oxygen, but if not present they can use another energy source), growing in different sources (soil, corn silage and other feedstuffs, TMR, feces and milk), and their transmission routes.

Samples were collected at three heights in the silage: central (one meter from the surface); peripheral or close to the tarp end (the most external 15 cm of visibly damaged silage usually discarded before feeding); and the area immediately below (15 to 30 cm) which is ends up in the TMR.

Main species of spore formers isolated from different sources

The dominant facultative anaerobic and anaerobic microorganism species were mainly Clostridium (26 species) and Paenibacillus (12 species); C. tyrobutyricum, P. macerans and P. thermophilus were present in all potential sources.

Spore count in different sources

High variability in spore counts was observed:

- Silages: low-contaminated samples (below 3.0 log spores/g) corresponded mainly to the center of the silage (89.5%); most samples with high contamination (above 5.0 spores/g) were collected in the periphery of the silage (63.8%) and the area immediately below (34.5%).

- Other feedstuffs (dried forages and concentrates): the spore content was 1.40 to 3.06 log spores/g.

- TMR: The spore population oscillated between 2.11 and 5.89 log spores/g.

- Manure: The spore content was 2.15 to 5.32 log spores/g.

- Bulk tank: Milk samples contained between 1.79 and 3.82 log spores/l.

Contamination pathways from the silage to the bulk tank

The higher the presence of mold in silage, the higher the spore count in the TMR. Similarly, the more spores in the TMR, the higher the spore count in feces and, finally, the higher the number of spores in feces, the higher the spore count in milk.

This contamination chain was related to farm management practices: farms that discarded contaminated silage before preparing the ration had lower spore counts in the TMR (below 4.0 log spores/g), feces and milk compared to those that partially discarded or did not discard contaminated silage.

With respect to the manure, when the spore count of the TMR was greater than 4.5 log spores/g, there was a contamination greater than 3.0 log spores/g. Nineteen farms of the 21 that had feces contamination with more than 4.0 log spores/g, did not clean the silage surface properly before preparing the ration, and most of them had a spore count in the TMR greater than 4.0 log spores/g.

A high number of spores in the manure can oftentimes be explained by sampling methodology, some studies indicate however that under certain circumstances (stress, wounds, etc.), clostridium in the digestive tract can multiply and cause problems.

Through the contaminated feces the spores passed into the cow’s teats and from there to the milk in the bulk tank.

The importance of good management practices

Data from this study confirm the role of feces in contaminating milk with spores and the importance of adequate management practices to reduce silage deterioration, and thus stop the first route of contamination. Good silage management practices helped reduce the incidence of aerobic deterioration and consequently, having less spoiled silage resulted in less spore contamination of the TMR, feces and milk.

It should also be noted that farms that had cleaning protocols in place before putting up silage also took measures before and after milking to reduce the risk of microbial contamination of milk.

Conclusion

The degree of silage contamination is the most important factor determining contamination that exists in the farm’s bulk tank. When contaminated silage is incorporated into the TMR, the risk of having higher spore counts in manure increases.

While it is very difficult to control spore contamination throughout the milk production chain, the risk on farms can be reduced by implementing good management practices, starting with good silage making practices all the way to milking.

Reference

Borreani G, Ferrero F, Nucera D, Casale M, Piano S, Tabacco E. 2019. Dairy farm management practices and the risk of contamination of tank milk from Clostridium spp. and Paenibacillus spp. spores in silage, total mixed ration, dairy cow feces, and raw milk. J. Dairy Sci. 102:8273–8289.

© 2021 Dairy Knowledge Center. All Rights Reserved.