Álvaro García

Historical perspective

Wheat bran is among the earliest recorded byproducts used in cattle feeding, with origins that parallel the rise of cereal milling across the Mediterranean, Middle East, and Europe. In traditional agro-pastoral systems of the MENA region, where wheat and barley were staple crops, bran from local stone mills was routinely fed to cattle, buffalo, and small ruminants as a supplement to forages and crop residues. As industrial flour production expanded in Europe and later North America during the 18th and 19th centuries, bran became a readily available, palatable, and nutritionally balanced feed for dairy cows and draft animals. Long before the development of modern oilseed meals or synthetic supplements, wheat bran served as a key “concentrate feed,” valued for its fermentable fiber, moderate crude protein, and mild laxative effect. Early dairy texts frequently referred to “bran mashes” as standard rations, underscoring its key role in bridging the nutritional gap between coarse forages and grain-based feeding systems. In this broader context, wheat bran can be regarded as one of the foundational byproducts in the global evolution of dairy nutrition, from Mediterranean mills to modern intensive dairies.

What is wheat bran and how it differs from “midds”?

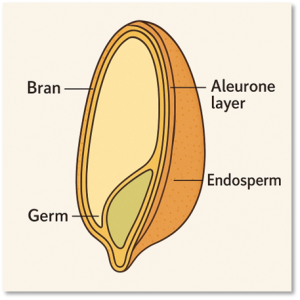

Wheat bran is the outer pericarp (seed coat) removed during flour milling. It is typically sold as a loose, flaky meal or in pellets; color and particle size vary with wheat class and the mill. You will also see wheat middlings (“midds”) on spec sheets, this is a broader by-product stream containing fine particles of bran, shorts, germ, some flour, and tailings, rather than pure bran. That distinction matters because nutrient density and the fiber-to-starch ratio differ markedly between the two.

If you look at the wheat kernel diagram to the right, the wheat middlings (midds) are not a single anatomical layer but a mixture of particles originating from several adjacent regions of the kernel produced during roller milling. In practical terms, bran represents the coarse, outer fibrous fraction, while middlings capture the transition zone between the bran and the starchy endosperm. This gives middlings a slightly higher energy and protein content but lower fiber than bran. Because of this compositional overlap, nutrient variability between mills can be substantial, and precise feed formulation should rely on recent analytical data (especially for crude protein, NDF, and phosphorus).

Relationship between Wheat Kernel Parts, Bran, and Middlings Composition |

|||

Kernel part |

Included in wheat bran? |

Included in wheat midds? |

Notes |

Bran (pericarp + seed coat/testa) |

✅ Yes |

✅ Partly |

Coarse outer flakes make up most of the bran; fine fragments enter the midds. |

Aleurone layer |

✅ Yes (technically part of bran) |

✅ Yes |

Midds often rich in aleurone—an important source of protein and phosphorus. |

Endosperm |

❌ (very little) |

✅ Yes |

Fine floury particles that escape full separation end up in midds. |

Germ (embryo) |

❌ |

✅ Some |

Small germ fragments contribute oil, vitamins, and variability. |

So, visually:

- Wheat bran = mostly the outer brown layer (pericarp + aleurone).

- Wheat middlings = everything between the pure endosperm (flour) and pure bran—a blend of fine bran bits, aleurone, germ, and small endosperm particles.

In other words, if you shaded the interface zone between the bran and endosperm in the image above, that is roughly where the “midds” come from. During milling, that transitional layer is scraped off in fine particles rather than flakes, giving middlings their softer texture and lighter color. These fractions retain more starch and digestible energy than bran but are still richer in fiber and minerals than pure flour, which explains their intermediate nutritional value and broad use in dairy and monogastric feeds. In many regions, particularly Australia, New Zealand, and parts of Asia and Africa, this same material is marketed as wheat pollard (“semitín” or semita, de trigo in much of South America), a finer, flourier grade of bran used in poultry, pig, and dairy rations as an economical source of fermentable fiber, moderate protein, and residual starch. Pollard’s slightly higher energy density compared with bran makes it especially suitable for inclusion in grower and finisher diets or as part of balanced concentrates in mixed farming systems.

Nutrient profile—strengths and limits

On a dry-matter basis, wheat bran typically supplies moderate crude protein (15–18%), high NDF (40–50%) that’s quite fermentable (rich in hemicellulose), modest starch, and meaningful phosphorus with very low calcium, often around 11 g P/kg DM vs 1–2 g Ca/kg DM. Expect ash to run higher than cereal grains and fat to be lower. Take-home message: bran is a protein–fiber–phosphorus package, not much of an energy concentrate like corn. Balance Ca:P and dietary cation–anion carefully.

Its composition varies with the type of wheat used (e.g., durum vs. common wheat), the extraction rate, and whether you are buying straight bran or a blended midds (pollard) product. Always ask for a recent Certificate of Analysis (COA) and, if possible, verify key nutrients such as phosphorus (P) and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) on incoming loads. Because bran and midds concentrate the outer layers of the grain, they can also accumulate mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol (DON/vomitoxin), zearalenone, or aflatoxins when sourced from contaminated wheat. For this reason, periodic mycotoxin screening, especially after wet harvest seasons or when buying from multiple mills, helps ensure safety and consistency in dairy and monogastric diets.

Quality and handling notes

- Physical form: Pelleting improves flow and reduces sorting; fine, dusty bran can bridge in augers and invites sorting in TMRs.

- Shelf life: Low fat means low rancidity risk but keep it dry; caking elevates mold risk.

- Anti-nutritional factors: Bran’s phosphorus is phytate-bound; without phytase it is poorly available and elevates manure P. (If you use feed phytase elsewhere in your program, you know this story well.)

What does dairy cow research say?

Feeding ~12–20% durum wheat bran

Feeding ~12–20% durum wheat bran in concentrate (replacing part of cereal and/or by-products) did not depress milk, improved oxidative status, and even enhanced cheese yield/quality metrics in a pasture-linked cheesemaking chain (Bonanno et al. 2019). In summary bran can be neutral to positive for production while adding sustainability and product-quality angles, especially with durum streams common around Mediterranean mills.

Wheat middlings + urea as the RDP base (US, mid-lactation herds)

When diets were equalized for CP, NDF, starch, and ME, a protein premix built around wheat middlings + urea supported similar milk production and BW to a rumen-protected soybean meal diet; a specialty fermentation product out-performed both on DMI and ECM, but midds + urea itself held its own as a cost-effective RDP source (Fessenden S.W. et al. 2020).

Replacing corn/starch with wheat midds (reduced-starch diets)

A reduced-starch TMR created by swapping part of corn grain + SBM for wheat middlings (plus whole cottonseed) held milk fat but reduced milk and protein yield and worsened feed conversion vs a normal-starch control; adding amylase gave little benefit (Ferraretto et al. 2011). Read this as a ceiling warning: midds can replace some starch, but heavy replacement costs milk unless the energy gap is addressed.

Prepartum use (transition cows)

In a 2×2 study testing straw source (wheat vs oat) and energy supplement (corn vs wheat bran at 10% of diet), cows on wheat straw + wheat bran prepartum showed better early-postpartum energy balance, higher Wk1–3 milk, and fewer health issues than some comparators, suggesting bran can be a useful, safe energy–fiber carrier in dry/close-up diets when managed well (Iqbal Z. et al. 2020).

Practical formulation—where bran fits!

- Transition diets: 5–10% of DM prepartum helps deliver fermentable fiber with moderate protein and keeps starch in check; watch potassium and DCAD in close-up diets.

- Mid-lactation cost control: 5–12% of DM (or 10–25% of concentrate) can replace part of corn/soy when the price per unit of RDP + NDF + P is favorable. Pair with adequate energy (corn grain, fats) to avoid the reduced-starch penalty seen when midds displace too much starch.

- Cheese/value-chains: Where durum bran is common (Italy, MENA durum belts), inclusion around 10–20% of concentrate can bring oxidative/cheese-processing benefits without hurting yield.

How much? Safe working ranges (DM basis)

- Close-up (−21 to 0 d): 5–10% (careful with DCAD, K, and Ca:P).

- Fresh/early lactation: 5–8% (keep peNDF and energy density high; avoid excessive reduction of dietary starch).

- Mid–late lactation: 5–12% typical; upper limit depends on total starch, NDF, and energy, avoid using midds as a near-complete grain substitute unless other energy sources are added.

Balancing rules that make-or-break performance

- Energy density first. If midds/bran displace starch, replace that energy elsewhere (high-fermentability corn, protected fats) to protect milk and protein yield.

- Calcium and phosphorus. Bran is P-rich and Ca-poor → add limestone and monitor manure P; if you already use phytase, you can reduce mineral P.

- Protein form. Midds contribute mostly RDP; pair with adequate RUP if milk protein is a priority (and do not forget urea’s limits).

- Physical effectiveness. Fine, dusty bran is not “effective fiber.” Maintain peNDF with forages; pelleted bran reduces sorting but does not replace long particles.

- QA & variability. Confirm you are buying bran vs midds/pollard, ask for P, NDF, and moisture on the COA, and check loads when switching mills or wheat class.

Example inclusion scenarios

- Cost-savvy mid-lactation TMR (31% NDF, 26% starch): 8–10% wheat midds, corn grain adjusted to hold starch, limestone up to meet Ca, RUP source maintained (e.g., heat-treated soy) → expect neutral milk, stable components if energy is held.

- Mediterranean cheese chain: 10–12% durum bran in concentrate for stall-fed cows with conserved forages; monitor milk oxidative markers and curd yield, often neutral-to-positive outcomes.

- Close-up diet: 6–8% bran with wheat straw base; keep K/DCAD within target and ensure Ca supply. Watch NEFA/BHBA and early-lactation milk, can be favorable vs corn.

Bottom line

Wheat bran (and midds) are reliable, cost-effective carriers of RDP, fermentable fiber, and phosphorus. They are NOT free energy, push inclusion without compensating energy and you will reduce milk/protein. Use wheat bran or middlings as a controllable ingredient option to help manage or reduce ration costs during mid-lactation without sacrificing performance. Done right, bran can improve sustainability metrics and, in some systems, even product quality.

The full list of references used in this article is available upon request.

© 2025 Dellait Knowledge Center. All Rights Reserved.